|

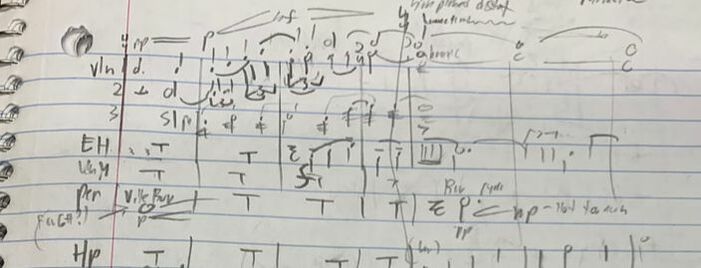

When composing, there are times when I simply don't know what to do. After several years of great teachers and my own experiences, I've found 14 key ways of "unstucking" myself. 1.) Free Writing – Just keep writing and go with the flow. If you feel like you’ve wandered off too far, stop. You can choose to evaluate what you’ve written, what works and what doesn’t work, or continue exploring unexpected twists and turns the piece could go. You might find that your free writing leads to the discovery of an exciting, more interesting idea. If not, you at least have something to work with now! Sometimes what you create in your free writing can be applied elsewhere throughout the piece, not just the section you’re working on. 2.) Mini Variations – In the last couple measures where you are stuck, try rewriting them in as many different ways as possible. When I do this, I like to have a goal number of 20, but sometimes you only need to write 5 to get on the right track. All you need to ask yourself is “what if?” You may choose to make the variations relevant to previous or forthcoming material or entirely new! 3.) Map it Out – Draw out some possible ways the piece could continue. Formal and structural diagrams help show how what you’re working on relates to the “big picture.” Another possibility is to map out one parameter of the music like register or dynamics. Graphic notation like this helps me write down the gist of what I’m thinking without having to translate it to proper music notation. 4.) Verbalize – Talk out loud to yourself (or a friend) about why this section is bothering you, why you feel stuck, and what ideas you have to keep moving forward. The overall goal is to develop a solution you can take back to the drawing board. When I do this, I really like to record myself for about 10-15 minutes and then listen back. This gives the opportunity to respond to my own thoughts in real time! When I do this exercise, I like to either walk around my home, lay down with my back on the floor (I found a comfortable rug), or take a nice, hot shower. If you’re going to record your shower lectures make sure your phone is waterproof or in a sealed container! 5.) Going Pitchless – Write down a passage without using pitch. This is a big help for me when the unlimited variety of pitches feels very overwhelming and I can’t make up my mind. I use college-ruled line paper to do this and keep the ruled lines horizontal. However, some prefer to do this where the paper is landscape, the ruled lines are vertical, and the distance between two lines represents one beat. 6.) New Tunnel Vision – If you feel like you’ve been focusing all your energy on one particular aspect (harmony, rhythm, instrumentation, form, registration), forget about it! Place all your energy some place you haven’t been looking or experimenting. 7.) Opposites – Try doing the completely opposite thing of your initial idea. You never know what you’ll find! This can help eliminate any prior assumptions you’ve made about the piece that are getting in your way. Even if you don’t like the results, it will get you to “think outside the box.” 8.) Scope – Try looking at the piece at a global level. Looking too locally can lead to distracting tunnel vision. Instead of focusing on a single, exact moment, focus on a phrase, section, part, movement, etc. Consider its broader relevance. 9.) Reorder – Sometimes it’s not that any of the music is bad, incorrect, or inappropriate for the piece, but that it is coming at the wrong time. Try seeing the events in a new order, a different flowing through time. This was the subject of my most recent lesson, and it 100% changed my outlook for the piece. Does this idea happen to early? Should this part go like X, Y, Z, or like Y, Z, X? 10.) Copying – Copy your piece by hand or work on the engraving. I wouldn’t recommend doing the whole thing, but maybe 5-10 measures before where you’re struggling. A teacher once told me that when experiencing a problem in a piece, the real problem is actually often a little earlier. You could also copy an earlier, completed part of the piece you’re proud of. I find that I can be more productive when I find something to be excited about. Morton Feldman claimed that copying his own work was the most valuable advice John Cage gave to him. 11.) Analyze – Create an analysis of the music you have already written for the piece. Why does it work? What makes a certain moment or section special? Are there any curious, unexpected patterns? Are there any problems? Sometimes the answers to a good future are in the past. 12.) Core Decision Thinking – Shrink the task down to a few limited choices, namely five options: a.) Do what you’re already doing. b.) Do something new. c.) Do something you did earlier. d.) Silence e.) End the piece 13.) Move On – Simply put, work on a different section. Personally, I have a bad habit of just endlessly revising the music I’ve already written. The last few years I’ve slowly developed an ability to write the music that I think comes after a section I am struggling with. Sometimes knowing “where you are going to” is more important than “where you are coming from.” Often times I write sections of a piece in an order different from how they are heard. Some days I feel like I can hear all the piece at once, but I have to sift and sort to learn what comes first, next, then, last, etc. 14.) Step Away – Sometimes it really is more productive to get away from it and clear your mind. This is especially true if you’ve been beaning your head against the wall for a while. Get up and be active, walk around, take the dog outside, meet a friend for lunch, run some errands, etc. Anything to get your head out of the misery of “stuckness.”

2 Comments

|

Archives

July 2023

|