|

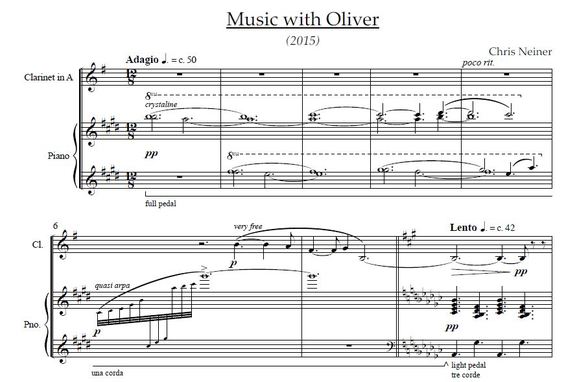

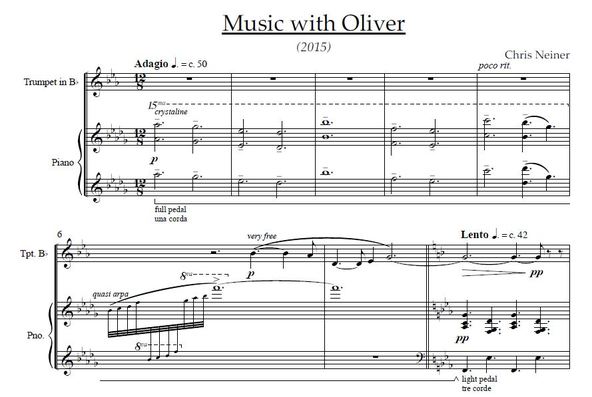

I’ve recently had the opportunity to arrange Toy Chest and Music with Oliver, but I feel like it would be more accurate to say I have been “recomposing” them. In the process of losing the original ensemble, I gain a new one and likewise lose and gain compositional opportunities: interesting textures, instrumental timbres, extended techniques, etc. For me, the new opportunities must be explored and discovered, yet I cannot forget the purpose and sound of the first version. Balancing new opportunities and original intent is a delicate, frustrating, but rewarding process. Toy Chest: https://soundcloud.com/chris-neiner/toy-chest-2015 When arranging Toy Chest for flute, clarinet, and piano, I struggled to arrange the horn and violin parts for the woodwinds. (I had decided to not alter the piano part.) Often, the horn part was too low for either the flute or the clarinet. Passages utilizing violin pizzicato and muted horn needed equivalent color ideas in the later version. An early solution was to use the bass clarinet, but I quickly abandoned this idea in favor of using the lowest possible note on the typical Bb clarinet. There was never a good place for the clarinetist to switch between instruments and only using bass clarinet seemed like a bad idea. However, I did find the use of the piccolo to be very applicable. Color issues were solved by using slap tongue on the clarinet and pizzicato technique on the flute. Both techniques produce sharp, percussive pops by quickly articulating notes with greater use of the tongue. Opportunity seeking led me to exploit the dexterity of the clarinet with rapid descending scales at a pace not idiomatic for horn or violin. Toy Chest was arranged specifically for my friend Samantha Tartamella. She and her ensemble will premiere the arrangement on April 24 at Bowling Green University Music with Oliver: https://soundcloud.com/chris-neiner/music-with-oliver-ssmf-2015 Musical changes in Music for Oliver are best explained with score excerpts that show the differences quite clearly. Clarinet Version: Trumpet Version: In the trumpet version, the lowered key required me to alter the accompaniment to best match my original intentions of register. Ultimately, this meant creating reinforced octaves at the begging of the score, moving the run in m. 6 upwards, and using less dense chords at the beginning of the Lento section.

For exemplary arrangement models, I look to Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin for piano or chamber orchestra and Jennifer Higdon’s Fanfare Ritmico for orchestra or wind ensemble.

1 Comment

“If you develop an ear for sounds that are musical it is like developing an ego. You begin to refuse sounds that are not musical and that way cut yourself off from a good deal of experience.”

― John Cage No one is born with musical preferences, it all develops gradually in a rich mix of life experiences. As we grow up, we hear music of our culture in society. We hear sororities, chord progressions, timbre, forms, balances of consonances and dissonances, styles and aesthetics, etc. As we are repeatedly exposed to similar music we develop a familiarity with it that is both comfortable and enjoyable. We develop a preference; certain sounds in music become normal and easy while those heard much rarer strange and challenging. Society communicates us its musical values and dislikes, beginning our first definitions of what is good music and not good music. “The first question I ask myself when something doesn't seem to be beautiful is why do I think it's not beautiful. And very shortly you discover that there is no reason.” ― John Cage With enough exposure outside are immediate preference over time we change and the definition of good music, even music itself, broadens. Beethoven’s late period is a common example; much of the music from his later life was found to be too dissonant and uncomfortable. Now, it’s performed, no one flinches an eyelash, and it’s highly praised by many. With great fortune, our personal curiosities and interests, societal and individual, lead us to discover music and define how we feel about it. “If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, then eight. Then sixteen. Then thirty-two. Eventually one discovers that it is not boring at all.” ― John Cage Our immediacy to define music as bad is what fascinates me. It’s a product of our cultural values, experiences, growth, and I think an unfortunate, instinctive-like closed mindedness, a “fight or flight” mechanism set in the brain to try and prevent us from interacting with something perceived as dangerous. It isn’t that some music is bad, it’s that we haven’t developed a way to internally come to terms with the music. But if you ask John Cage, there will always be good music! |

Archives

July 2023

|